‘It was November-- the month of crimson sunsets, parting birds, deep, sad hymns of the sea, passionate wind—songs in the pines.’

~L.M. Montgomery~

November started with a fairly changeable, mild westerly airflow in which a succession of fronts spread eastwards across the UK at times. There were no named storms and there was the continuing dryness of parts of the country. The skies were awashed with shades of orange and pink in a spectacular autumn sunset just in time for the drive home from work. The colours were caused by light molecules penetrating longer wavelengths of light. Only yellow, orange and red colours were able to get through, creating these spectacular sunsets.

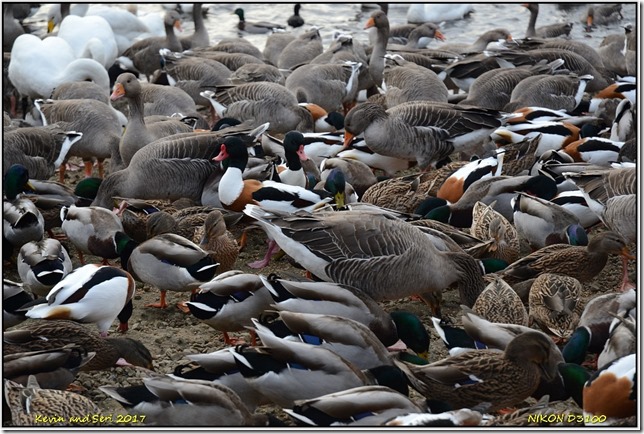

Slimbridge WWT was our first destination for the month. We’d a long tour because there were road works being carried out on the main route into the reserve. Thankfully, the very tiny single track had been tarmacked and made driving through bearable. As usual, we headed straight to Rushy Hide and was greeted by hundreds of Common or Northern Pintails, a winter visitor from Iceland and Scandinavia. Their presence in large numbers had pushed the Teals to congregate right at the back of the lake.

Drake pintails were stunning. They were sleek and slender, with long protruding tail feathers which gave them their common name. They appeared pale grey overall, but sported a lovely chocolate-coloured head with a white stripe extending up from breast to behind each eye. Under their tails, they were black and cream, and in flight a white, black and rufous bar was revealed on each wing. The females were mottled tan overall, but still appeared to be sleeker and more pointed than other female ducks. In flight, they showed a brown wing bar edged with white. Both had blue-grey bills.

They foraged mostly on plant materials like seeds, roots and tubers of water plants taken whilst dabbling, upending in the shallow water .Their long necks enabled them to reach deeper than other dabbling ducks. Feeding was mainly in the evening and at night, and invertebrates were added to the diet during the breeding season. During the day, they were either resting, preening or dozing.

Walking or running with a slight waddle, the Pintails were quite agile on land, but were most graceful and acrobatic in flight. They were able to achieve great speeds while flying, earning them the nickname ‘the Greyhound of the Air’. They also earned the title ‘nomads of the skies’ due to their extensive migratory routes. They were quiet ducks, but the males might emit a mellow, whistled ‘kwee’ or ‘kwee-hee’ while the females produced a hoarse, muffled ‘quack’. Unfortunately, as a ‘quarry’ species which meant that it could be legally shot in winter which I found very disturbing for such stunning ducks.

After taking hundreds of photographs of the Pintails, we headed for the next hide. We heard a loud dreamy song and looked up and saw this Mistle Thrush singing its heart out on the tree-top. I hoped a storm won’t be appearing soon because the far reaching songs could only be heard during stormy weather, hence its alternative name of Stormcock. The Thrush was important in propagating the mistletoe, an aerial parasite, which needed its seed to be deposited on the branches of suitable trees. The highly nutritious fruits were favoured by the birds, which digested the flesh leaving the sticky seeds to be excreted, possibly in a suitable location for germination.

At Martin Smith Hide, carpets of Wigeons were feeding on the tack field in their distinctive moving formation. Many migrated to the UK in winter were from Iceland, Scandinavia and Russia. The calls of the males were a rather evocative whistling ‘weee-ooo’ sound which carried far across the grazing marshes. The females had a much harsher growl-like calls. Being vegetarian, they were grazing on the short grasses, stems and roots. When foraging, they gathered in densely packed flocks, covering the grassy swards with their bodies, and spilling forward like an incoming tide. Each had the unusual combination of a small bill and an exceedingly strong jawbone, which enabled them to pull up the grass with great vigour and made use of the bill’s cutting edge at the same time.

Suddenly for no apparent reason, they took wing, accompanied by a wild chorus and a mighty roar of wings. Within moments, the sky was filled with fowl. Flight after flight swept past, turning and twisting at high speed and maintaining close contact. Others climbed high, silhouetted against the sky, before returning to the tack field. As each flight swept down diagonally their wings produced a startling rushing sound. And at the moment of landing the drakes revealed dazzling white wing-patches.

When the Wigeons landed back on the Tack field, a couple of Curlews were among them. Their mottled-brown plumage made for effective camouflage against the marshland and tack piece, which meant they could go about their business unnoticed, prying invertebrates such as ragworms and insects with their purpose built curved bills. An old Scottish name for the Curlew was ‘whaup’ or ‘great whaup’. Their evocative calls had been immortalised in a poem, The Seafarer, dating back to 1000AD although it may be even older.

‘I take my gladness in the… sound of the curlew instead of the laughter of men.’

We made a pit stop at Willow Hide and the usual birds were taking turns at the feeders. There were Chaffinches, Tree sparrows, Blue and Great Tits. Dunnocks and Moorhens were feeding on the floor. In the opposite hide, the Robbie Garnett Hide, we had a close views of a Black Tailed Godwit in its winter plumage feeding, probing the mud with its long bill for worms and bivalve molluscs. In winter, it had a smooth grey-brown neck, breast and upperparts.

A pair of Greenland White-fronted Goose was having a conversation nearby. They’d a large white patch at the front of the head, around the beak and bold black bars on the belly. The salt-and-pepper markings on the breast was why they were colloquially called ‘Specklebelly’ in North America. Their legs were orange with pink bills. They bred in Western Greenland, migrating during September and October via staging grounds in Iceland to winter here, before returning in April. Crossing the 2700m high Greenland ice cap was a remarkable feat of endurance for a large bird. They had shrill, cackle like calls. The geese grazed and foraged on a range of plant materials taking roots, tubers, shoots and leaves. This pair was much more interested in preening themselves.

Then we walked back into the main reserve and headed straight to South Lake. A large flock of Black Tailed Godwits were fast asleep in the shallow part of the lagoon. They’d one of their legs lifted and tucked close to their bodies, turned their heads with their bills tucked beneath their scapulars. They were now in their winter plumage with dull brown feathers with white undersides and long, nearly black heads. Loafing and feeding across the water edge were good numbers of teal. shoveler, shelduck, mallard and tufted ducks. Then it was time for us to call it a day.

When we arrived home, we could smell sulphur in the air. Someone had let off fireworks early for Guy Fawkes Night. Also known as Bonfire Night, it was an annual commemoration observed on 5 November. Its history began with the events of 5 November 1605, when Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had placed beneath the House of Lords. Celebrating the fact that King James I had survived the attempt on his life, people lit bonfires around London, and months later the introduction of the Observance of 5th November Act enforced an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure.

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration, but as it carried strong Protestant religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate-figures, such as the Pope. Towards the end of the 18th century reports appear of children begging for money with effigies of Guy Fawkes and 5 November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day. In the 1850s changing attitudes resulted in the toning down of the anti-Catholic rhetoric, and the Observance of 5th November Act was repealed in 1859. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night was usually celebrated at large organised events, centred on a bonfire and extravagant firework displays. We spent the night watching the displays by our neighbours from the comfort of our home.

We didn’t launched any fireworks, waved sparklers or burnt bonfires but we still took lots of photographs. We enjoyed our neighbours fireworks offerings from the comfort of our casa and some were very spectacular. Some shoot straight up before exploding, others whirled in spirals, some shattered into thousands of sparks, others tumbled like waterfalls or floated in glittering shower. At times, we just don’t know where to look. There were whishes, whirrs, booms, whizzes, zooms and the skies were continuously brightly lit alongside spontaneous very loud bangs. Tons of smoke drifted and the smell of sulphur was quite overpowering. I couldn’t helped oohing and aaahing at such extravagance. The next morning, I came across piles of spent fireworks on my way to the bus-stop.

We made our first annual trip to Donna Nook. We left very early at 7.45 am so that we could get a parking space at the Stonebridge car-park. It was 3.7C and the sun was beginning to show its face. We came across beautiful sunrises as we criss-crossed the country but there was no place to stop and take photographs. We stopped at Wragby for a comfort break and slowed down near Yarburgh where we saw a Short-eared owl quartering when we drove past 2 years ago. Thankfully, all the road-works had been completed and we arrived at our destination at 10.28 am and wasn’t surprised to see the car-park nearly full and it wasn’t even the weekend.

After parking and wrapping up very warm, we waddled our way to the viewing point. Both of us looked like the Michelin man. It was freezing and the high winds didn’t helped either. We noticed that the red flags were out and stopped at the RAF observation box and enquired if there were anything going on as Donna Nook was also a military range. He confirmed that there were military exercises being carried out. Whoop…whoop. Babe had brought his radio scanner along and turned it on. Fingers crossed something exciting would turned up. I also just found out that Donna Nook was reputedly named after a Spanish ship The Donna which ran aground here during the 1588 Spanish armada.

As we trekked along the chestnut-paling fence that ran the entire length, pups of different stages of growth with their protective mothers were scattered along the beach, among the sand-dunes and reed-beds. Their whimpering cries were echoing around us. It was still early in the season although the first pup was born on Friday the 13th of October, beating the earliest dune pup by 9 days. We checked out the board and there were 452 bulls, 812 cows and 527 pups in the reserve. Another half way to go. We walked on when a large flock of Brent Geese flew off in long V-shaped formations called ‘skeins’. They were only found here in the winter.

Meanwhile, there were plenty of heart warming scenes where mothers were nursing their pups. It was lovely watching the intimate interactions between them. A bond was formed between mother and pup at birth, and she could recognised her pup from its call and smell. Mothers were encouraging the pups to feed by scratching their faces. Pups suckled for 3 weeks during which their weight tripled and gradually lost their pale coat. In the meantime, the mothers lost half of their body fat during lactation as they weren’t feeding.

Each pup I encountered was cuter than the one before, looking at me with their glossy black eyes like coal. Appearing in shining white colour when born, called languno, which kept them warm until they developed an insulating layer of blubber from their mother’s milk. They kept this distinct white coat for two weeks + when the fur darkened and began to shed as they matured. After 16+ days, at the weaning stage, the pups lost their white coat and had the unique grey/dark grey pelage and patterning that remained the same through adulthood. These adorable pups were very close to the fence, checking out the visitors who were busy checking them out, under the watchful eyes of their possessive mothers. If anyone got too close, the warning hisses and waving flippers were issued.

Nearby, the males (Bulls) were slumbering about, rolling, scratching and snoozing in the mud-banks and sand-dunes bidding their time and waiting for the pups to be weaned and the females (Cows) to be in season and ready to mate. The males tended to be darker than females and had the noticeably arched ‘Roman‘ nose. When the females were ready, their uterus developed a fluid-filled sack containing an egg and hormonal changes made her receptive to the advances made by the males. For the time being, the males were quite content to be together. It was very peaceful at the moment, although there were a few scraps when if another male tress-passed their territory.

We didn’t see any births but there must had been a few earlier because there were plenty of afterbirths laying around with pups still stained from the yellow amniotic fluid. They were relatively helpless, and relied totally on their mother’s milk for 16-21 days. The milk was more than 50% fat, and the pups grew very quickly, depositing a thick layer of blubber to protect them from the cold. During this period of intensive care, the mother lost 65 kg of her own body weight. When she was forced to return to the sea to feed, the pup remained at the breeding ground for another 2 weeks before hunger forced them to head out to sea to feed.

We noticed chaos out on the mudflats by the sea, as waders and wildfowls were being flushed by raptors such as Merlins, Marsh Harriers and Kestrels. Flanked by 2 major estuaries, the Humber and the Wash, provided vast mudflats for migrating waders and overwintering wildfowl to feed and rest. On the mudflats, among the dunes, slacks and inter-tidal areas characterised by sedges and rushes, there were large flocks of Golden Plovers, Shelducks Lapwings, Knots and Dunlins feeding. Unfortunately, their presence attracted these raptors regularly flushing them into several full air displays, swirling around before settling down again to feed.

Suddenly the radio scanner cackled and, we heard some very loud rumblings overhead and a flawless grey machine appeared in the horizon and zoomed across the sea. It was a F15, an American twin engine, all weather tactical fighter aircraft which was the backbone for the Air Force’s air superiority and homeland defense missions. The beach had multiple targets on it and markers denoting the range and distance and between targets,. The aim of the pilot was to fly at a designated height and speed fire their laser to the target, then pulled up and bank off to the left, north, over the sea. The practice went on for quite some time.

F15 was the Muhammad Ali of the skies, showing its all weather air superiority with the proven design that was undefeated in air-to-air combat. The two engines provided 58.000 pounds of thrust which enabled it to exceed speeds of Mach 2.5.The pilot knew we were photographing him and he piloted the F15 at a sharp angle, accelerating quickly while climbing in altitude which allowed us to get the perfect shot. All you could hear was our cameras rattling away. Then it disappeared back to its base at RAF Lakenheath.

The wildlife were unfazed by the planes and the flares. I think they were used to it as Donna Nook was an active military range since WWW1 and was established as a protection point from Zeppelins trying to enter the Humber area. The seals didn’t even bat an eyelid. Meanwhile, swarms of Goldfinches were feeding on the dead thistles and teasels with their high-pitched rapid twitterings. There were mobs of starlings roaming about. This Redshank was feeding quietly along the mud-bank, probing its bill into the mud for insects, earthworms, molluscs and crustaceans.

Babe’s scanner started crackling again. Suddenly, we heard a loud screech and then a thundering noise, ascending in decibels. Another jet whizzed through the blue Lincolnshire sky. It was a Typhoon doing its practice run. Wow… 2 different jets in a day. I couldn’t help grinning and we got our cameras ready. The schedule was the same as the F15, targeting the markers with laser. I wished it was night when you could get a better photograph of the lasers being directed to the target. But, beggars can’t be choosers.

The pilot did some acrobatic manoeuvers as it glided through the sky after lasering its target. It was a very expensive exercise because the cost of flying a Typhoon for one hour was believed to be in the region of £3,875!!! As well as conducting 24/7 year-round protection of the UK’s sovereign airspace on Quick Reaction Alert, these jets were regularly deployed on air policing missions to protect Baltic airspace, operating at extremely high readiness no matter what the conditions. I guess that was money well spent. After about an hour of practice, it climbed in altitude and disappeared from our sight. What a way to go.

We were also on the lookout for our favourite seal, Ropeneck, so named by wardens who found her in 2000 entangled in discarded netting and was clearly in distressed. Kudos to the Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust wardens with assistance from RAF Donna Nook for cutting her free. But the netting had cut a very deep wound in her neck which was still visible even today. We asked one of the wardens who informed us that she hadn’t arrived yet. We then headed back to the car for lunch. It was lovely to be away from the bitterly cold and wet winds. After finishing our picnic, we decided to head home. It was too cold and too crowded and we’d already seen everything. We planned to come again in about a fortnight when the breeding season will be at its peak.. As we were leaving the car-park, a Little Egret flew over to wish us a safe journey home.

After the long trip, you would expected us to be putting our feet up. But, we didn’t. There were just too many exciting things to do and see. We loaded up the car again and headed north. This time to Martin Mere WWT in Lancashire. We left the casa at 9.13 am and it was raining with the mercury at 9.3C. The traffic was running smoothly and we kept on double-checking the route to make sure that we weren’t on the toll road. Once bitten, twice shy. It was a lovely drive as the countryside was bathed in spectacular autumnal colours. As soon as we parked the car, we were greeted by skeins of Pink-footed geese flying and calling overhead. The air was full of flight and feathers. The cacophony of calls mingled with the whirr of wings overhead. What a welcome.

“Two sounds of autumn are unmistakable…the hurrying rustle of crisp leaves blown along the street…by a gusty wind, and the gabble of a flock of migrating geese.”

~Hal Borland~

We wrapped up warm as the Northerlies had put a chill in the air. We headed straight to the newly opened interactive Discovery Hide and managed to squeeze in the nearly-full capacity hide. We looked out of the window and this was what we saw. A family of Whooper Swans were bonding. Elegant and blinding in their whiteness, they arrived en masse to feed and established family bonds, providing an unrivalled show. Throughout the day, they spent the time bathing, preening and filter feeding in the shallow water in the low winter sunlight.

They had made the 500 mile migration from Iceland to escape the biting Arctic weather by spending the winter here. Their evocative calls heralded winter in many parts of the country. The crossing was probably the longest seas crossing undertaken by any swan species. They were powerful fliers and lost an estimated 25%of their body fat whilst undertaking the migration. Many of the juveniles were only 3-4 months old when they made this incredible journey. The first Whooper swan arrived here on the 1st October and Martin Mere could hosted upwards of 2K from November to March, with higher numbers recorded in the coldest of winters. This was about 7% of the Icelandic Whooper population.

“An assembly of swans is one of our most moving wildlife pageants. The jostling family groups of snow-white adults and greyish cygnets have a mesmeric beauty, while the bird’s evocative bugling calls suit frosty weather to a tee.”

~Kate Humble~

Whooper swans spent the summer breeding in Iceland, Scandinavia, northern Russia and northern Asia. If you looked closely, you noticed that some Whoopers were stained from the iron rich waters of their breeding grounds. Unlike the Mute swans which had a point to their tails, they had square-ended tails when up-ending. They tend to hold their neck erect while swimming. They also had long bills which was mostly yellow with a black tip. When they flew in, their wing beats made slight hissing sound. We were mesmerised by these graceful ‘swanfall’ which kept on coming and coming and …

When a family of swans flew in to join the group, they were very animated and vocal, flapping their wings about. They’d very loud trumpeting calls which sounded a bit like an old fashioned car horns. They congregated for added protection. Shortly after landing, they participated in greeting or triumph ceremonies, which included head bobbing, calling and wing flapping. Due to the closeness of these interactions, they easily transitioned to either sexual or aggressiveness interactions. Aggression towards others could be displayed by a combination of ground staring, where the neck was arched and wings were spread slightly, bow-spitting, where the neck was held forward, and carpal flapping, where the wings flagged vigorously. In the case of conspecific competition , a ‘water-boiling’ display occurred, in which both swans outstretched their wings before physical attacks were initiated by both parties.

When it was time for them to leave, several pre-flights signals were noted. Common movements included ‘head pumping’, increased four-syllabic calling and wing flapping. They continued to increase signalling, building excitement and allowing synchronization to occur during take off. When they took to the air, the sight and sound made a stunning spectacle. There was a great deal of goose action coming and going throughout the day. The reserve provided these birds with a safe environment after the hazards of their epic journey which they might experience setbacks ranging from storms to finding themselves blown off course.

Nearby, large flocks of Pink-footed geese were resting on the marsh, hidden by the tall reed beds. Squadrons of cackling Pinkies were flying in filling the sky, their bellies full from a day’s foraging and landing in the marsh. They fed in the arable farmland on post-harvest cereal stubbles and sugar beet tops. Farmers were encouraged to leave them in the fields, rather than ploughing them in, as this diverted the geese away from the growing crops. They decorated the sky with these long V-shaped skeins as they travelled daily between their feeding and roosting areas. We saw wave after repeat-wave of geese skeins arriving . Dozens of skeins stacked vertically upon each other and stretching almost half a km across formed an instinct black haze of pumping feathers against the sky. When they came to land they lost attitude by banking sharply from side to side, an action known as whiffling.

The Greenland/Iceland Pinkies population wintered exclusively here in Great Britain. Often colloquially referred to as pinkfoot, they were known for their loud honking calls, high-pitched, double-noted ang-ank, which were most prominent during their V-formation flight. I wished they were resting close to the hide so that I could see them clearly. Pink-footed geese were short-necked and compact with distinctively short pink bills and their trademarked pink legs and feet. In flight, they were easily identified by their brownish neck and underparts with soft grey back and upperwings.

In the folklore of northern England, the cries of migrating geese flying by night were linked to Gabriel Ratchets. ‘Gabriel’ was derived from the name of the angel of death, the ‘gabble ‘ of geese, or the medieval word ‘gabbe’ meaning corpse. ‘Ratchet’ originated from the English word ‘raecc’ meaning ‘a dog that hunts by scent’. In his Notes on the Folklore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders (1876) William Henderson suggested the ‘beliefs in a pack of spectral hounds’ originated from ‘the strange un-earthly cries, so like yelping dogs, uttered by wildfowl on their passage southwards.’ What superstitious attributes these migrating geese brought with them.

We’d about 3 hours to kill before the feeding bonanza started. We made a pit stop at the very busy bird-feeders near the binocular shop. I was hoping to see a Brambling but there were only Greenfinches, Goldfinches, Robins, Blue and Great tits. Large flocks of Long-Tailed tits were roaming among the tree tops, their excited calls echoing around us. We were very surprised to see that the Swan link hide no longer existed and was replaced with a couple of screens. From here, we spotted Shelducks, Wigeons, Teals, and Mallards having a siesta among the Greylags.

At Janet Kear Hide, we were entertained by at least a dozen rats under the bird-feeders, scavenging the seeds that had fallen to the ground. They were very nervous and would often scampered off into a hole under a pile of wood at the slightest noise. On the bird-feeder, the usual culprits were there joined by Chaffinches and Tree sparrows. We then walked through a wooded path where lots of fungi were popping out towards the Unite Utilities Hide which afforded views across Woodend Marsh . It was quite busy here because a few raptors such as the Marsh Harriers, Buzzards and Sparrowhawks were often seen hunting. We didn’t see any but we were chuffed to bits when a family of Whoopers flew right across our window. We were sitting on the 3rd floor.

Then we checked out the Harrier Hide. There was nothing much here although the silence was occasionally broken by the loud bursts of the Cetti’s warblers. We also noticed a new walk below the hide which looped through the reed-beds onto Utilities hide. We then turned back and did a quick walk through the main captive area. Since it was winter, most of the birds weren’t out and about. We were very lucky to have seen the latest species that was unveiled here in April 2017. It was a pair of African spoonbills.

Located in the Wow (Weird or Wonderful) area of the grounds, the pair were in an aviary with the Avocets and White-faced whistling ducks. They had only recently being paired together as one was from Blackpool Zoo and the other was from Birdland in Gloucestershire. Their bodies were predominantly white, except for their legs, face, and a long, thin beak which ended in a flat, extended bulge resembling a spoon. They were usually silent, except for the occasional grunt when alarmed.

We enjoyed watching the Whistling ducks busy preening each other. Mutual preening was highly developed, and was important for permanent pair bonding. They vocalised frequently with distinctive high-pitched, multisyllabic whistles which sounded very un-ducklike. They were also known as tree ducks due to their habit of perching on tree branches but today they were content to be sitting on the rocks by the pool, grooming each other. When alarmed, they froze and stood tall in a distinctive erect posture while watching intently. It was so cute to watch.

We left as more and more people entered the aviary as they were trying to shelter from the rain. We came across a Black Swan which followed us expecting some seeds. It gave us the eye and huffed off when it saw us empty handed. We went back to the car to warm our cockles with Cheese and onion pasties and washed down with steaming mugs of coffee. We were frozen while walking out in the open. Above us, skeins of Pink-footed geese were still flying in. Then we walked back into the warm Discovery Hide to get a seat for the feeding extravaganza. It was beginning to fill up.

The 3 pm feed pulls in the crowd, for both visitors and wildfowl. We sat with great anticipation as the swans, waders and ducks milled around the Mere, squabbling like teenagers and displaying to future mates. The noise from thousands of wildfowl were deafening. A warden appeared with a barrow of grain, and spread it just feet from the hide and before she hardly had time to turn her back, the birds descended, jostled and feasted noisily. The ducks and pigeons were packed tightly in front followed by the Greylags and then the Whoopers. It was mayhem. This feeding ritual was performed daily until the lengthening hours of daylight drew the migrants back to Iceland to breed.

From troubles of the world I turn to ducks,

Beautiful comical things

Sleeping or curled

Their heads beneath white wings

By water cool,

Or finding curious things

To eat in various mucks

Beneath the pool,

Tails uppermost, or waddling

Sailor-like on the shores

Of ponds, or paddling

- Left! Right! - with fanlike feet

Which are for steady oars

When they (white galleys) float

Each bird a boat

Rippling at will the sweet

Wide waterway…

When night is fallen you creep

Upstairs, but drakes and dillies

Nest with pale water-stars.

Moonbeams and shadow bars,

And water-lilies:

Fearful too much to sleep

Since they've no locks

To click against the teeth

Of weasel and fox.

And warm beneath

Are eggs of cloudy green

Whence hungry rats and lean

Would stealthily suck

New life, but for the mien

The hold ferocious mien

Of the mother-duck.

~F.W.Harvey ‘Ducks~

Then there was a stampede heading to Harrier Hide for another extravaganza and this time it was the Starlings turn. Early this month, the media was awashed with photographs of spectacular displays from the Starlings spectacular performance at Martin Mere. It was so popular that the current winter closing time was being extended for this viewing. The Hide was so packed that it was standing room only. We decided to join the others outside in the freezing cold. Hundreds were already here, waiting for the magic to happen. We could feel the anticipation vibrating in the air.

As the sun began to dip slowly on the horizon, small dark specks appeared in the sky above the reed-beds. Just a few at first, and then gradually, the specks were joined by others coming from all directions, until there was a huge dark cloud pulsating in the sky. Thousands had congregated in twisting, swirling flocks above their night-time roosting sites. They swooped, soared and swirled, creating ephemeral, ever-changing shapes in the sky, like smoke in a breeze. They were dashing back and forth at break-neck speed, splitting off into two or three groups before swarming together again like an aerial ballroom dance that only they knew the moves.

There were times when the birds formed a rising crescendo, then swooped down, and then up and across the sky, like a ribbon, wrapping around itself. If nature had ever produced a more perfect thing than the mesmerizing beauty of a starling swarm, I have yet to encounter it. No other phenomenon had ever awed me quite like this yet, unless it was the Northern Lights It made me forget everything else in the world except the brief moment of Mother nature unfolding before me.

Then, they started cascading down into their roost like a waterfall. Here, they chattered to each other, before snuggling down for the night. Roosting alongside thousands of others meant they shared body heat to keep warm during the long cold nights and exchange information about the best spot for tomorrow’s breakfast.

The ambience was changing At the fading of the light. I could feel a cool embrace, The coming of the night.

In the sky, a great commotion Countless starlings did I see A swirling murmuration In perfect symmetry.

Fluid moving patterns Writ wide across the sky, Oh, but the joy of it To watch these starlings fly.

An ever changing tapestry, It was ballet in the air. A wonder to behold I could but stand, and stare.

I felt like applauding at the finale. Late arrivals flew straight into the roost, like arrows, which were quite impressive. Then it was a slow walk back in the dark. Reserve wardens walked everyone back to the visitor centre after the display to the exit as the building closed at 4.30 pm. I kept on looking back to see strays still flying in. When we walked past the Meer, we could hear the murmurs and one or two quacks in the dark as the wildfowl settled for the night. Then we joined the exodus as hundreds of cars were trying to leave. We took our time and when we drove through the exit gate, we wished the natives ‘Bonne nuit’.’

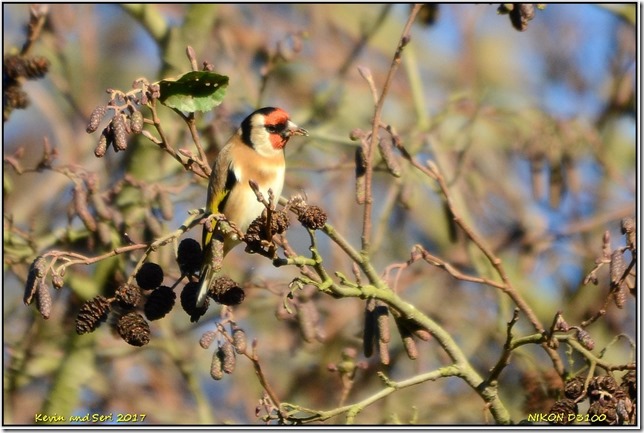

During the weekend, we checked out our favourite playground to see what the natives were up to and also to see if there was any murmurations going on. Along the path, we heard the familiar delightful liquid twittering songs and calls. We looked up and saw a charm of Goldfinches feeding on the fir cones. Their long fine beaks allow them to extract inaccessible seeds from the cones. They were not restful birds because while they were feeding, they continually looked around checking for threats. From time to time, they used their outstretched wings to balance counteract the buffeting of the wind. With their blood-red faces, golden wing bars and bubbling twitters, Goldfinches were a visual and auditory delight. During late winter, when such vibrancy remained a scarce commodity, they brought colour and excitement.

We made a pit stop at Baldwin Hide and there was nothing about so off to East Marsh Hide. We don’t have to wait long when we spotted a Water rail out and about along the reed-beds. The bird rarely emerged from dense reed-beds and marshes with a thick vegetation cover, and tended to be shy and skulking. This secretive bird was much more often heard than it was seen. The calls of a Water Rail was extremely un-bird-like, and never failed to take me by surprise! They produced a wide range of loud squealing and snorting noises, traditionally known as ‘sharming’, which sounded like an alarmed piglet.

Water rails had chestnut-brown and black upperparts, grey face and underparts and black-and-white barred flanks, a long red bill tiny and tiny cocked tail. The birds themselves were extremely hard to see, preferring to stay hidden in thick vegetation. Winter was the best time to see them, partly due to the larger number around, and also because they were sometimes forced to forage in the open when the water surface was frozen solid. They fed on land or in water, probing with their bill and ate anything from small fish and freshwater shrimps to frogs, snails, or the roots and shoots of aquatic plants. Their slender legs and toes were adapted for walking on floating plants, allowing them to slip quickly through the marshy vegetation without being seen.

Then a Little grebe flew in and landed on the island in front of the hide. The liveliest hunters among the herons, they fed by walking through water and snapping at prey, or by running and agitating the water with their feet to disturb prey, flushing them into the open where the sharp-eyed bird could strike at them. It was thought that their yellow feet aided this process, being more obvious to potential preys than all dark feet would be in the sediment-filled water. They were highly dependent on visual cues when hunting and their feeding was highly affected if the water was not clear. They fed primarily on small fish, but bivalves, crustaceans, and other invertebrates were also consumed.

We slowly made our way to Carlton Hide when the Gulls started flying off to Draycote Waters to roost. We were hoping that the skies would become alive at dusk. We were quite excited to see a few birds flying in, Just a few at first, and gradually, they were joined by others coming from all directions, until there was about 200 birds swooping in unison, appearing like a shoal of fish. Unfortunately, the flying display had been relatively short, with the flock dropping early into the reed-beds. A few late-comers went straight into the reed-beds to join their companions for the night.

It was quite disheartening to see such a dismal display when a few years back, we’d seen at least 5K gathered, wheeled and swooped in dark clouds over and into the reed-beds. Perhaps, there was another roosting site elsewhere or they were put off when there were major works being carried out to open a new reed-bed. The RSPB warned that the Starling population had fallen by more than 80% in recent years and now on the UK critical list birds most at risk. The decline was put down to the loss of permanent pasture, increased use of farm chemicals and a shortage of food and nesting sites in many parts of the country. It had became a cliche to describe the massive decline as ‘the miner’s canary’. But that was just what they were, a warning that we can’t go on treating nature as an optional extra to our lives.

“In November, the trees are standing all sticks and bones. Without their leaves, how lovely they are, spreading their arms like dancers. They know it is time to be still”

~Cynthia Rylant~

No comments:

Post a Comment