We welcomed St. George’s Day, the patron saint of England, and the birth of Prince Louis with a trip to our favourite playground. There was a pause from the torrential misery-inducing rains which continued to drench the country as heavy downpours showed no sign of abating. In between sunny spells and scattered showers, we made our way through the very lush reserve. Everything had gone ‘whooosh’. Primroses were still flowering profusely on the shady hedge banks and now joined by the fragrant blue-violet sweet viola.

I saw a Robin with moss in its beak. There must be a nest nearby and it was waiting patiently for us to move away. In mild winter, the courtship had started in January but the breeding season began in March. They paired only for the duration of the breeding season.The care of the fledged young was left to the male, while the female prepared herself for the next nesting efforts. Robins had 2 broods a year. Three successful broods a year was not uncommon, and in a good year even four were known.

At Baldwin Hide, we were pleased to see an Oystercatcher sitting on nest, which was usually a depression in the ground. She was being kept company by another nesting Coot which I found endearing as both were well-known for their aggressiveness and for being very territorial. From time-to-time, the Oystercatcher’s partner flew in with its distinctive and shrill, piping call ’kleep, kleep’ calls trailing behind it. It was lovely watching the pair with their bright, orange bill, pink coloured legs, and black and white plumage bonding. The sexes were similar in appearance, although males had shorter, thicker bills.

Oystercatchers were historically known as the ‘sea pie’. The name was superseded during the late 18th and early 19th century, after Mark Catesby in his Natural History of Carolina (1731) coined this name for the American species Haematopus palliatus. While the American Oystercatcher fed upon ‘clams and coon-oysters’, oysters weren’t featured in the diet of the European species. Mussel picker and Mussel cracker were more accurate names. The fierce orange bills worked as a pair of pincers, prising mussels and limpets off rocks and removing the food.

We continued on to the very busy East Marsh Hide and managed to find a seat. There was so much going on that we don’t know where to point the camera. A Garganey had brought everyone into the hide. This male easily recognised with a broad white stripe over the eye was feeding by ‘dabbling’ for plant materials and insects. Garganeys were scarce and a very secretive breeding duck in the UK and listed as a Schedule 1 species.

A pair of Redshank flew in alerting us with their loud piping calls ‘teu-hu-hu’ with longer and more accented first syllable. These adults were in breeding plumage with grey-brown upperparts, spotted darker brown and black. On the upper-wing, the secondary flight feathers were white and visible in flight. At first, they walked along the shores, pecking regularly, occasionally probing, jabbing and sweeping through the water with their bills. Then the male performed a courtship display by rising and falling with vibrating wings. The female was very impressed with the display and let him have his wicked ways

Then a family of Mallard with 8 adorable ducklings appeared and swam close to the hide. They were cute little balls of down with clove-brown backs, relieved by 4 yellow patches. They were only a few days old but the sooner they got to the water to feed, the better were their chances of survival. They can’t survive without their mother, and took 50-60 days before they fledged and became independent. The ducklings fed themselves as soon as they reached the water, but needed to learn what was edible, such as water fleas, insects and duckweed. They depended on their mother for warmth. She brood them regularly, particularly at night, as they were easily chilled in the cold weather.

A Blackcap from the right side of the hide popped up to see what was going on. Adult males displayed the black cap that gave the species their common name, while females had a chestnut-brown cap. According to Babe, it had a nest nearby because he’d seen it flying in and out from the shrubby undergrowth. A summer visitor from Germany and north-east Europe, it had a delightful fluting song, earning the name ‘northern nightingale’.

After a couple of hours, we made our way to Ted Jury Hide. Near the now-abandoned badger set, we were entertained by this Whitethroat singing its heart out. He fluffed out his white throat feathers to produce the distinctive ‘jowled’ effect. A summer visitor and passage migrant, he stopped singing when he saw us and darted rapidly in and out of the bushes, while flicking and cocking its long tail. It popped up with a tiny fluff on its beak and flew off to the nearby bramble-covered bushes and flitting into cover. Then he perched at the top of the bush, and glared at us with a rapid churring call. It was a sign for us to leave.

At the end of the month, we made another trip to Brandon Marsh. Before we left, I took a photograph of this Mistle thrush fledgling waiting patiently to be fed. I had seen both parents flying in to feed the downy chick, pale and heavily spotted on the upperparts. It was dependent on the parents for 15-20 days after fledging and were mainly fed on invertebrates, often collected from low foliage or under bushes rather than in the grassland preferred by the adults. The chick would accompany the parents until the onset of winter.

We headed straight to Baldwin Hide when we heard the familiar high pitched ‘tsee, tsee’ calls. We followed the calls and spotted a ‘mouse-like’ bird with a down-curved bill and stiff tail, moving in a spiral around a tree-trunk. Then it flew off to the next tree, repeating the process, starting at the bottom again. The intricately patterned brown plumage of a Treecreeper was an ideal camouflage for a bird working its way up a tree-trunk. It was busy foraging for insects and their larvae by probing the crevices of tree barks with its long thin bills.

We made ourselves at home in the hide. The Oystercatcher and Coot was still sitting on eggs. The air was filled with Sandmartins and Swallows, showing off their aerial displays while catching insects in flight. The Swallows were easily identifiable with their dark, glossy blue-black backs, red throats, pale underparts and long tail steamers. These summer visitors had just arrived from Africa and they were busy feeding, gathering their strength before getting ready to attract a mate. From time to time, they flew low, skimming the surface of the lake for a drink.

We were also delighted to see the courting behaviour of a pair of Common Terns. The male had already chosen the nesting site and was luring the female with a fish, calling in their high-pitched squeaky calls. This behaviour established a pair-bond, and showed the female that her mate was capable of catching fish on demand. An important skill when there were hungry nestlings to feed. After a pair bond was formed, the male fed her and then only they began to copulate. Fingers-crossed, we will be seeing plenty of action as there were 3 floating pontoons for the rest of the Common Terns to use.

We were so captivated by the Swallows and Common Terns that we missed seeing a Common Sandpiper flying in to the island with the nesting Oystercatcher and Coot. Something splashing in the water caught our attention and then only realised what it was. After having a wash, it started foraging for insects, worms and molluscs along the banks, frequently bopping up and down, known as ‘teetering’. When it was disturbed by another Coot, it flew off with rapid, shallow wing beats on stiff, bowed wings. In flight, the striking white wing-bar was visible. It was also a sign for us to head home too.

At home, we were greeted by the yummy smells of chicken rendang, a traditional Malaysian dish, warming in the oven. There was an uproar when MasterChef judges complained during the quarter finals of the reality cooking show that the chicken skin in the rendang wasn’t crispy. Stewing over the comments, foodies, prime ministers and everyday Malaysians, vented their fury on social media. Because, “crispy” was never associated with rendang – a rich dry curry that required meat to be slow-cooked in spices and coconut milk. I’d never watched the programme but I was proud of how fellow Malaysians bonded together when their traditional food was insulted.

Chicken rendang

- 1.5kg Chicken cut into 12 pieces

- 500ml Milk from starch of 1½ grated coconut with 500ml (2 cups) water

- 110g Toasted coconut paste (kerisik)

- Salt to taste

- Sugar to taste

- 1 Turmeric leaf, sliced

For Spice Paste

- 8 Shallots, skin peeled

- 3 cloves Garlic, skin peeled

- 8 stalks Lemongrass, sliced

- ¾ inch Ginger, skin peeled

- ¾ inch Fresh turmeric, skin peeled

- 6 Red chillies, deseeded

- 5 Chilli padi, deseeded

- 1½ tbsp Coriander powder

- 1 tbsp Powdered aniseed

- 1 tsp Cumin powder

- 2 tbsp Chilli paste

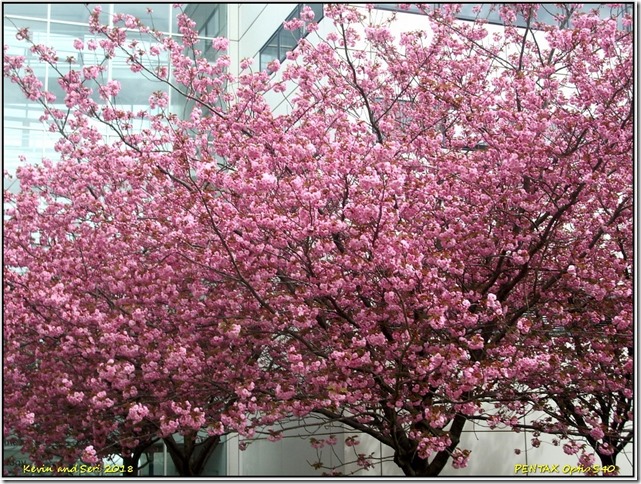

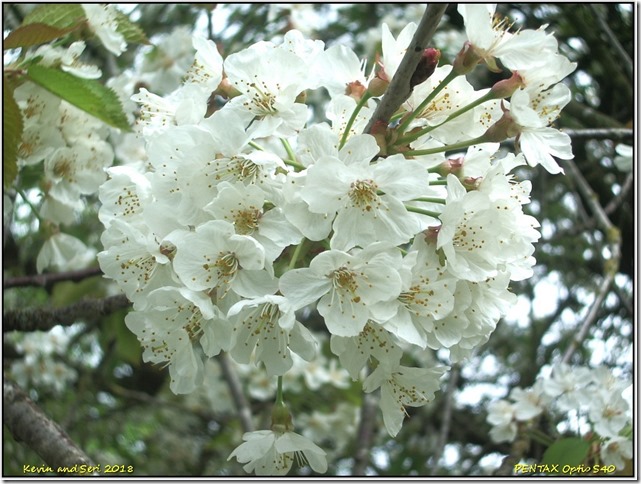

During my lunch-break at work, it was heaven to be wandering around the campus grounds with the trees drooping with cherry blossoms. It was a sight to behold with the trees in full riotous blooms. Clouds of these ornamental blossoms were at their absolute peak thanks to the combination of sunny days and cold nights. The white blossoms were out first and it was hard to concentrate when they were blooming outside my window. Eventually these white or pink, lacy blossoms fluttered down and carpeting the ground. Due to their very short flowering time, the blossoms were often seen as a metaphor for life itself, luminous and beautiful, yet fleeting and ephemeral.

The Japanese poet Otomo no Kuronushi wrote in the 9th century,

‘Every-one feels grief when cherry blossoms scatter’.

*quote by Christopher Morley